History

It's a lifetime passion. Writing about it is a new level of learning. It requires something different of me. Please read my essay about "Perspective".

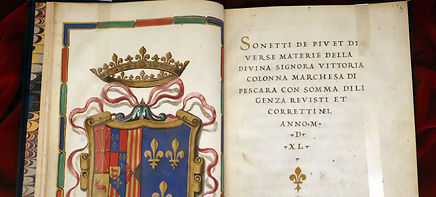

Colonna and Her Poem

in Concept ...

“Scrivo sol per sfogar l'interna doglia” - Rime vedovili

Vittoria Colonna was a Roman noblewoman of the sixteenth century. She is known in history as a poet. She wrote sonnets, inspired by love and by religion. A sonnet is more than one poem; an author is more than one person scribbling. They both are whole communities. A sonnet evokes hundreds of others. It evokes a tradition and many other authors. A poet speaks about and for and to complex networks of people, contemporary and historical. Vittoria was a friend to Castiglione, Michelangelo, and Pietro Bembo. Her husband was a trusted general serving Emperor Charles V. Her sonnets were read far and wide. Her work was lauded by Lodovico Ariosto in an encomium in the “Orlando Furioso”. She herself was a community.

Colonna and her poetry form a nice dual lens for the study of her epoch, one of the most dynamic in European history, bridging the times of Lorenzo the Magnificent in Florence, Savonarola, and the Borgia pope, Alexander VI to the times of Grand Duke Cosimo I, Emperor Charles V, and Pope Paul III and the Council of Trent. In her lifetime, she witnessed the rise of Martin Luther. She sought out the company of Renée d'Esté, Duchess of Ferrara, who had hosted John Calvin only a few months earlier. Though she never became Protestant, she, and her friend Michelangelo, were sympathetic to the “spirituali” in Rome, who sought reform within the Catholic church.

Florence in 1494

The Friar Who Defied the Renaissance

in Concept ...

Florence in 1494 was a nexus of extraordinary people and extraordinary events. This generation and this place are etched into the mind of European civilization in a way that few are. It is my belief that neither a simple chronicle of the time nor a biography of Girolamo Savonarola will capture enough of the impact of this city, this time, and this unusual man. One needs to tour the city and have an introduction to the characters.

“For my part, I am not sure; my mind is not made up one way or the other … but to conclude, I say this: if he was good we have seen in our day a great prophet; if bad, a very great man ….”

- Francesco Guicciardini, Florentine statesman and historian, (1483-1540)

QUICK TOPICS

Excerpts from the blog:

A couple of artists have been on my mind, a couple of hard-working artists. I’ve been reading the famous letters of one. One passage stood out. He’s about twenty-seven, and he has gone on a trip to see the country of a favourite artist. “I did go to Courrières last winter,” he writes, “I went on a walking tour in the Pas-de-Calais …. I had just ten francs in my pocket and because I had started out by taking the train, that was soon gone, and as I was on the road for a week, it was rather a gruelling trip. Anyway, I saw Courrières and the outside of M. Jules Breton’s studio.” He was too shy to knock on the door.

He continues on his trip. “I earned a few crusts here and there en route in exchange for a picture or a drawing or two I had in my bag. But when my ten francs ran out I tried to bivouac in the open the last three nights….” My body aches just reading it.

This artist repeats quite often his commitment to working hard. “Work” must be the most repeated verb in the collection. “So you see that I am working away hard ….”

“I saw something else during the trip,” he writes, “the weavers’ villages. The miners and the weavers still form a race somehow apart from other workers and artisans and I have much fellow-feeling for them …. And increasingly I find something touching and even pathetic in these poor humble workers ….” He wants to paint them.

Another artist was born centuries earlier in a humble section of his town, a neighbourhood called “Ognissanti”, after a thirteenth-century church there. At that time, the neighbourhood was inhabited by weavers and workers. His father had been a tanner but had become a gold-beater, which put him in contact with the artists and goldsmiths of the city.

The artist was a restless boy. Vasari says of him, “He was the son of Mariano Filipepi … who raised him very conscientiously and had him instructed in all those things usually taught to young boys during the years before they were placed in the shops. And although the boy learned everything he wanted to quite easily, he was nevertheless restless; he was never satisfied in school with reading, writing, and arithmetic. Disturbed by the boy’s whimsical mind, his father in desperation placed him with a goldsmith.” This was a fateful step. In those days, goldsmiths were close with painters, workers all, and the boy was taken by painting. Later he would add his art to the décor of the Ognissanti church itself. He never left that neighbourhood his entire life.

from #1180

QUICK TOPICS

Excerpts from the blog:

The Road to Carrara

The first time Michelangelo visited the marble quarries in Carrara, the fifteenth century hadn’t even reached its close, the High Renaissance was in full bloom, Mannerism and Baroque were waiting patiently in the wings – largely waiting for this young man to mature, – Raphael was a teenager, and Leonardo was working on his “Last Supper”, while designing weapons of war for the Sforza in Milan. Savonarola, the radical preacher, was running Florence – an episode I’ll be writing more about soon. Botticelli was in middle age, and was quite enthralled with Savonarola’s message, so much so, according to some, that he threw some of his own artwork into the great Bonfire of the Vanities earlier in the same year that Michelangelo visited Carrara.

Lorenzo de’ Medici had been Michelangelo’s first great patron. After Lorenzo had died, and after his son and successor, Piero, had been exiled from Florence, Michelangelo was forced to make other plans. His first stop was Bologna. But every ambitious artist of the day hoped to make their way to Rome. The Eternal City was resurgent, recovering from the rough years of the previous century and the early fifteenth century. The popes and Roman aristocracy were eager to rebuild the city in their image. The twenty-two-year-old Michelangelo already had achieved some renown as a sculptor. Next step: find his way to Rome.

How it came about was strange and fortuitous. On a visit back to Florence, Michelangelo fashioned a sleeping cupid from marble left over from another sculpture. The story goes that he contrived, upon the advice of a friend, to make the sculpture appear as though it were ancient and recently excavated. As Vasari puts it, “nor is there any reason to marvel at that, seeing that he had genius enough to do it, and even more.”

What followed was a bit of scandal, at least according to one version of the story. His friend sold it to a cardinal in Rome, and then shorted Michelangelo on the payment. The cardinal subsequently discovered it was modern and demanded his money back. This brought to light the friend’s deceit. There was outrage all around. The cupid did eventually find a home, and Michelangelo found his notoriety among the Roman aristocracy. That led in quick succession to his first extended stay in Rome and to the creation of the masterpiece that, among all his work, first stole my heart a long time ago.

from #1187

ergens anders